This project was conducted for a course on Human Information Interaction that I took during my final semester of Dalhousie University’s Master of Information program. As part of the coursework, we were to develop a “pilot study” or small-scale research project looking at a narrow aspect of human information behaviour (HIB).

HIB is widely studied. Literature typically divides this behaviour into three phases: discovery of an information need, seeking/searching for information to meet the need, and, finally, putting the information to use. Despite being a critical piece of the overall information behaviour process, information use behaviours are much less studied than the other two phases. In addition to exploring a set of research questions, my objective for the project was to see if my findings aligned with existing HIB literature on information use. Encouragingly, they did!

My project focused on how Facebook users utilize what they find in groups when making real-world decisions, and how they judge trustworthiness. I looked specifically at one large, closed Facebook interest group: Sounds like MLM but OK. The group’s preferred acronym is SLMLMBOK; you’ll see it referenced frequently in the rest of this post.

What is SLMLMBOK?

Sounds like MLM but OK is a closed Facebook group that, as of 19 April 2020, has over 164k members. Here’s how the admins describe the group:

We want this to be a safe and fun place to discuss and learn about multilevel marketing companies (MLMs) and their poor business structure, obnoxious marketing practices, and all around awful nature. This is also a place to vent about your #bossbabe “friends” you haven’t talked to since 5th grade but have a wonderful opportunity for you! *If you’re here to mock or troll consultants, you’re in the wrong place.*

Excerpt of SLMLMBOK Group Description, as of 2020/04/19

SLMLMBOK has a high level of activity, as might be expected for such a large group. There are upwards of 20 posts per day. Almost all posts get at least a couple of comments, and many generate comment chains that span in the hundreds. The frequency of activity increases the chance for members to encounter, and therefore potentially use, the information they find.

I decided to conduct a survey in this group because I have been a member for several years and have been consistently impressed by the richness of the group’s information landscape. Members share personal stories about their time working for MLMs. They post news articles about lawsuits and current goings-on. They provide support for members who have recently left MLMs. They upload statistics and income disclosures intended to be shared with those considering signing up with an MLM. More lighthearted content is also shared, including memes and videos that poke fun at MLMs and MLM leadership.

How was the study conducted?

I designed a multi-part survey around three research questions:

- How do members of the closed Facebook group Sounds like MLM but OK use information they encounter in the group to modify their behaviour?

- How do members evaluate the credibility of the information and/or information sharer?

- What role does this evaluation of credibility play in information use behaviours?

Group members were eligible to participate if they were 18 or over and had either been a distributor for an MLM themselves or had a close friend/family member who’s a distributor. Recruitment took place in mid-February 2020.

Participants were asked a mix of qualitative, open-ended questions and quantitative, closed-ended questions. At the end of the survey, they were shown two simulations of Facebook posts like what they might typically encounter in the group.

How were the data analyzed?

Central to this project’s design was Williamson’s model of ecological information use. Williamson’s model describes the ways in which different ecological factors (such as personal characteristics, socio-economic circumstances, values, lifestyle, and physical environments) impact how people use information (Williamson, 1998, p. 35).

In analyzing the data, I focused on the role of two factors — personal characteristics and values — in information use. Specifically, I examined how the personal characteristic of distributor status impacted use behaviours and evaluation of trustworthiness. I also took into account the respondents level of activity in the group. In measuring values, I derived key themes from participants’ responses to free-form questions about what criteria they use to judge if information is credible. I used both basic statistical analysis and thematic coding during the analysis phase.

Who participated?

There were 500 completed responses.

Participants were relatively similar within the demographic categories I asked about.

- Almost all respondents were female (n = 478)

- The majority of respondents were residents of the US (n = 389)

- Almost all were residents of primarily English-speaking Commonwealth or former Commonwealth countries including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States (n = 490)

- Most respondents were within the 25-40 age range (n = 348)

Almost all participants (92%) have or have had at least one friend or family member involved with an MLM. Of those participants, 76% know someone currently involved in an MLM.

Almost one third of participants were former distributors themselves, with most having left the group more than a year ago (44%) or more than 5 years ago (44%).

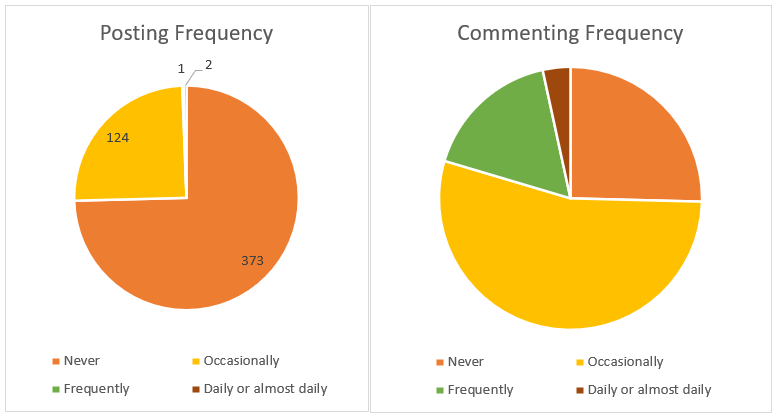

A lot of participants were lurkers who neither post nor comment. Overall, participants tended to comment more frequently than they made top-level posts.

How did they use information from Facebook in their everyday lives?

General use of info from Facebook

To provide a baseline idea of how survey respondents use information from other areas of Facebook, members were asked how frequently they make decisions based on what they read or see.

Generally, most participants (82%) reported that they get a lot of information from Facebook and other social media sites. A slightly lower percentage of lurkers (77%) and a slightly higher percentage of former distributors (90%) saw this as characteristics of themselves.

They were also asked to provide examples of the kinds of information they’re most likely to specifically check Facebook to find and use. The most common themes were support for parenting decisions, politics, reading reviews for restaurants and service providers, researching charities, food and cooking, networking, planning vacations, finding events, and checking out products based on Facebook ads.

Use of info from SLMLMBOK

All participants

All participants were asked for examples of times they had used information they came across in the group to try to help friends or family. Just over a third have used information from the group for this purpose. Some of the anecdotes mentioned sharing income disclosures and statistics, informing their loved ones of predatory and sometimes deceptive sales tactics, and relating to others the personal stories that were shared in the group. Many members used information from the group to dissuade their loved ones from joining an MLM or to persuade them to leave, with varying levels of success.

Lurkers

Among lurkers — participants who never posted or commented — the rate of information use was lower than for participants overall. Only 26% reported using information from the group in their interactions with others. There were no significant differences in the ways that lurkers used the information compared to all respondents. Most related times when they used statistics and income disclosures to try to help others or to draw attention to the negative outcomes that distributors often experience as a result of their MLM involvement.

Former distributors

Only 17% of former distributors reported using information from SLMLMBOK to make decisions about their own lives. Of those who did, the two most common themes were ceasing to support MLMS, whether financially or otherwise, and using tips and stories from the group as encouragement to talk with their former uplines and others in their lives about MLM involvement.

How did they evaluate credibility?

Before getting into participants’ evaluation of the simulated SLMLMBOK posts and comments, I asked participants how they typically judge if information is trustworthy.

I specifically inquired about the role that reputation (of both individuals and websites) plays in making this judgement.

Participants were much more confident in their ability to judge information based on their knowledge of a website’s reputation than their knowledge of a person’s.

- 48% were confident that they could often tell if information is true based on the website it comes from

- 23% said they can always tell based on the website’s reputation

- Only 17% of respondents were confident that they could often judge credibility based on what they know about the person who shared it

- <1% reported always being able to make this evaluation based on the person’s reputation

In responses to free-form questions, participants provided other examples of ways they evaluate how credible information is. Common themes were checking for corroboration with additional sources, judging based on the source’s reputation or the website domain (e.g., .com or .org), evaluating the quality of the evidence the source presents, using fact-checking websites like Snopes, and evaluating the tone and language the source uses. Infrequently, they reported confirming the information with experts they know or trusted people in their lives.

This preference for using online information when making value judgements is also borne out in Savolainen’s (2010) research on everyday life information seeking.

Judging simulated Facebook posts

To put these values to the test in an SLMLMBOK context, I created two mock-ups of posts similar to what participants might encounter during their regular browsing of the group.

Research by Jin, Phua, and Lee (2015) indicated that the degree of engagement (i.e., quantity of likes and comments) on a post can influence how credible participants find information to be. Other significant variables were the quality of the comments on the posts, the tone and style of writing, and the reputation of the source.

When crafting the posts, I manipulated several of the variables above to see if they impacted how participants perceived the posts. Post 1 contained a simulated link to an article by a well-known news source (Buzzfeed), but had little engagement and shallow comment depth.

By contrast, Post 2 had a link to a lesser known and potentially one-sided news source (mlmwatch.org), higher engagement, and a more information-rich comment.

The simulated posts were fairly simplistic, but the differences between them still provoked varying responses from participants. 80% said they’d seen similar content in the group before.

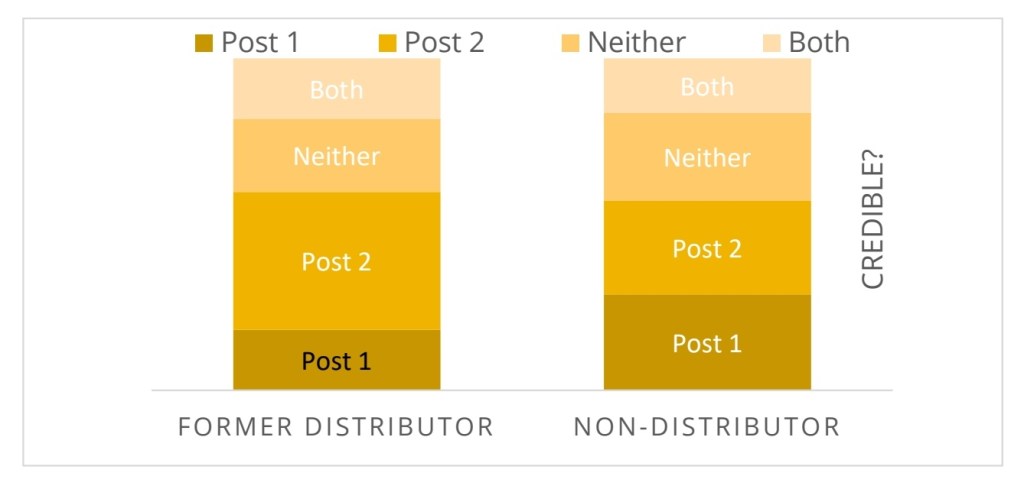

There was no overall consensus about which post was more credible, but separating the responses by distributor status revealed an interesting difference. Former distributors were more likely to view Post 2 as the more credible post, while those who had never been distributors roughly equally deemed Post 1, Post 2, and Neither post to be the most credible.

Unfortunately, I was unable to determine why this difference was so pronounced. Both distributors and non-distributors listed similar criteria for making the judgements they did:

- Reputation of the website source. Buzzfeed was incredibly polarizing. Most respondents named it as a deciding factor in their overall evaluation.

- Domain name. While .org was perceived as more trustworthy than .com, the mlmwatch website name seemed to some like it would produce more biased news

- Quality of the posts. Several responses specifically called out the greater level of detail in Maria Jane’s comment on Post 2 as a factor in their decision-making

Among those who voted that neither post seemed particularly credible, a frequently echoed comment was that they weren’t able to make a full determination without seeing the linked article or corroborating with additional sources.

These results ultimately aligned quite well with how participants described their means of judging trustworthiness in prior sections of the survey.

How were the research questions answered?

Research questions 1 and 2 were well supported by the data I gathered.

| Research Question | Results |

|---|---|

| 1. How do members of the closed Facebook group Sounds like MLM but OK use information they encounter in the group to modify their behaviour? | To help friends and family members • To educate others about predatory sales tactics • To dissuade a loved one from joining an MLM • To encourage a loved one to leave an MLM • To provide others with information about wage and income disclosures |

| 2. How do members evaluate the credibility of the information and/or information sharer? | Based on information sharer’s reputation • More commonly, based on a website’s reputation • Users also evaluate credibility based on their independent searching, the number of corroborating sources, the number of sources that an article cites, their evaluation of the article’s biases or hidden agenda |

| 3. What role does this evaluation of credibility play in information use behaviours? | Results inconclusive |

The data did not support a clear answer to research question 3. However, I believe this is an issue of study design rather than an evidence that there is no relationship between evaluation of credibility and how information gets used. Looking back, additional data could have been collected asking respondents if they would use either of the two posts to either make decisions for themselves or to help a friend or family member, or if they would use it for another purpose entirely.

Limitations

It should be noted that the intention of the assignment was not to produce a study with results that could be generalized. The scope of the assignment was to produce a “pilot study,” one that could serve as the basis for our future research if we were so inclined.

While the results of this study are quite encouraging and in line with HIB literature, the constraints of a 13-week semester and a full course load necessarily limited the complexity of analysis. If I had a larger chunk of time to work on this project (and, ideally, a research partner) I would have liked to add semi-structured interviews as a second means of collecting data.

Some of the factors that Williamson lays out in the ecological model of information use would have been very interesting to explore in interviews, particularly the ways in which lifestyle and socio-economic circumstances impact information use. By only looking at a couple of narrowly defined personal characteristics and values, it’s likely that more complex relationships and patterns remained unexplored. This was in alignment with expectations for the assignment, but for future research these relationships should be explored in depth.

It would also have been beneficial to more clearly ask participants about how they would (or wouldn’t) have used the information from the simulated posts in their daily lives. This question would receive more meaningful responses if more complex simulations were developed. The top-level posts didn’t have large amounts of text generated, so it’s possible participants would not have felt they had much information to go on.

Takeaways

I really enjoyed working on this project, and given more time I would have loved to explore these questions in greater depth. Social media sites like Facebook are such rich sources of information, whether it be in the form of more “serious” content like posts from official news sources or more frivolous content like memes and ironic groups.

Currently, many of us are staying home due to COVID-19. Our information sources have been almost exclusively narrowed to online interactions since in-person methods of information sharing are temporarily restricted. I imagine that a lot of our information exchanges are happening on social media right now, even moreso than before. This increased use offers an excellent opportunity to HIB researchers to explore digital information exchange. How do we use what we’re reading when we make choices? How do we choose what information we re-share to our timelines or directly relate to the people we know? Specifically, how do people make these choices about health-related information? How do we decide what’s worth our time and seems accurate to us? Does how we actually evaluate information align with how we think we do?

Now more than ever, these are pertinent questions to ask, and I hope that HIB researchers continue to do so.

Want to read the full report?

If you’re interested in reading the report in full, you can download a PDF copy below. The full report makes richer ties to HIB literature, has more in-depth results, and takes a deeper look at the implications of this research. Also, there are some graphs and tables that didn’t make an appearance in this post. If you like to visualize your data, you may want to take a look at the full report. However, the key findings and implications were discussed in the post above.

If you’d like to reference or re-use information from this post/file elsewhere, please get in touch with me prior to doing so.

References

Jin, S. V., Phua, J., & Lee, K. M. (2015). Telling stories about breastfeeding through Facebook:

The impact of user-generated content (UCG) on pro-breastfeeding attitudes. Computers

in Human Behavior, 46, 6-17. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.046

Savolainen, R. (2010). Source preference criteria in the context of everyday projects: Relevance

judgments made by prospective home buyers. Journal of Documentation, 66(1), 70-92.

http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.dal.ca/10.1108/00220411011016371

Williamson, K. (1998). Discovered by chance: The role of incidental information acquisition in an ecological model of information use. Library & Information Science Research, 20(1), 23-40. doi: 10.1016/S0740-8188(98)90004-4

Leave a comment